JP AFFLICK | CHASING THE HORIZON

We view the world in polarities.

We see them and we see us. We see those that can and those that can’t, the lucky and the unlucky, the privileged few and the deprived masses. At times, we view the simply unattainable with envy, changes that no amount of work or time or fortune may bestow upon us. But too often the focuses of our “I wish” have only one gaping chasm between us and possibility: ourselves.

With the utmost respect to him, there is nothing particularly special about JP Afflick. He doesn’t conjure swathes of adoring fans when stepping into the public eye, he doesn’t possess a bank balance to outclass a small European nation, he has no superhuman ability or innate talent that sets him peculiarly apart from you or I. But hidden beneath the genial and humble exterior is a story that drops jaws faster than JP drops clutches. JP and his brother, Mitch, are proof to us all that dreams are attainable, that the impossible is often anything but – JP is an Australian Champion, just half a mile an hour short of a world record holder, Mitch is just two mph slower and both are just nine weeks away from making even that bold claim a thing of the past.

JP and his younger brother were born into a fuel-injected life, with the smell of burned rubber and high-octane fuel as familiar as talcum powder and Napisan. Their father was into drag, but not the make-up and suspenders kind. Spending their childhood by the track, watching the old man tear up and down, the sound of the growling engines echoing through their little minds, the Afflick kids were instilled with a sense of speed and the thrill of its pursuit.

“My dad used to be the Australian drag racing champion in the ’70s, so we grew up around race tracks,” JP recounts of his early years. “Because dad raced bikes, we were always interested in them. I was riding a pushbike at three or four and had dirt bikes from the age of eight or nine. But I had a big pause until I was about 20. I had a road bike for a while when I lived on the Gold Coast, but there’s just that much traffic that you can’t make a mistake. You could be the best rider ever but then someone cleans you up. So I pretty much stayed away from road bikes – until now.”

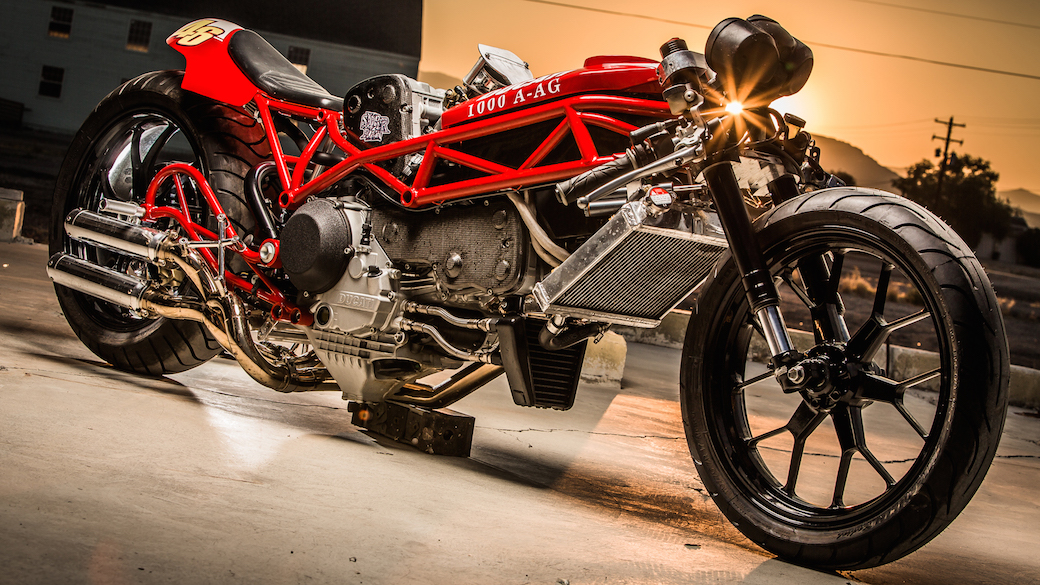

The two-wheeled, turbo-charged passion was genetic and, despite leaving the racing track behind many years before, a few years ago JP’s father took his two sons to Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah – the global Mecca of land speed racing. Drag racing, like many forms of motorsports, had become standardised. The bikes had to fit such a strict criterium that there was little scope for innovation and creativity and, just like the V8 or Formula 1 Supercars, there were only hairline differences from one bike to the next. But at Bonneville, anything was possible. People were making bikes in their back sheds, machining their own parts, adapting their bikes in shape, form and mechanics and letting their imaginations run wild. This was what motorbike racing was all about, and the Afflick clan was inspired.

It wasn’t until their return to Bonneville in 2012 that the trio decided it was time to join the tribe on the Salt Flats, not as spectators as they had been previously, but as competitors, those gladiators braving the expansive glare of the unforgiving plains to go faster than anyone else.

At this point, it is worth pausing to recognise exactly what it means to break a land speed record. There are those that reach for and surpass the sound barrier, travelling upwards of 760 miles per hour (1,223kph) in multi-million dollar rocketships crafted in wind tunnels by mad scientists and mathematicians. But the land speed record is as diverse as the vehicles used to achieve it. Cars, motorbikes, human-powered, wind-powered – the categories of competition are numerous. For JP and his family, their preferences dwell in the realms of sanity and, in December 2012, they bought a 100cc bike, their sights set firmly on reaching speeds at the uppermost limits of the engine’s capacity. To give the less mechanically-minded some perspective, the average 100cc bike tops out at around 60mph (100kph), so to hand-craft, tweak, refine and stretch the diminutive little engine to exceed the 100mph barrier is a spectacular feat of engineering. JP and Mitch are chasing different titles on the one bike and both are a favourable gust of wind short of making that dream come true.

“We were over at Bonneville and one night, after a dodgy microwave burrito and many beers, we thought, ‘we’ve got to get back over here and run a bike,'” remembers JP of their first steps. “But we fell back into life and it didn’t happen. In 2012, we went again as spectators, still having not done anything, and came back home and bought a little bike that Christmas. We started work on it from then – that was December 2012. It was a little dirt bike, a Honda CRF. For the class we wanted to go in, the 100cc, the world record is 110mph – you’re going fast, but you’re not going 400. The same bike we started with, we’ve just updated over the last few years. The first year was all about building a land speed bike, last year it was all about the power.”

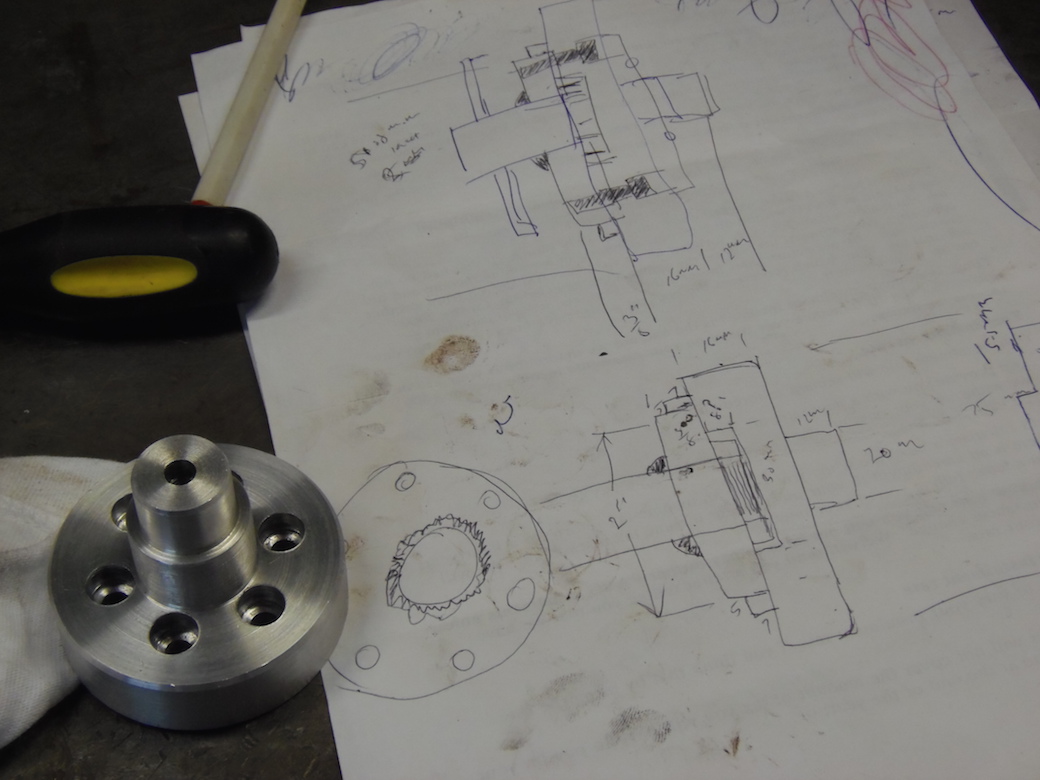

Tinkering away on weekends, reconnecting that family bond usually reserved for weddings, funerals and Christmases, in the mire of engine grease and iron filings, the three Afflicks created bespoke engine parts, machined and turned in their own garage, formed the cowling that would provide the aerodynamic cocoon into which they would fold themselves and eked every wisp of power they could out of the machinery.

A little to the south of Woop Woop, just behind the Back of Beyond and over six hours north of Adelaide lies Lake Gairdner. It is the Australian equivalent of Bonneville and a proving ground for Australia’s speed junkies. It was here, in the endless desolation of the salt-encrusted lake bed, that JP would set the Australian record at 109.5mph (176kph). Lake Gairdner is a test site. It serves well to familiarise themselves with the processes and methods of achieving a record, as well as the refinements needed to their equipment. Class records have been challenged and those attending the annual meets are very proud to be a part of the gathering. But Bonneville is where the glory lies, where the world of speed focuses its attention each year and where JP, his father and his brother will once again make the pilgrimage, but this time, with their bike.

“Bonneville has just celebrated a ‘Century of Speed’,” says JP, “so it’s been going for a hundred years now, whereas Lake Gairdner is only 25 years old. We have 200 competitors, whereas they have two and a half thousand. We’ve just shipped our bike to Bonneville and we head over in nine weeks. And yeah, it’s the Mecca, it’s the Monaco of Formula 1.”

So much in the land speed community is different. There are the big shots going for the big numbers, but there are the back yard hobbyists, guys just like JP and his family, who have built bikes up from nothing on the smell of an oily rag. Because of this, there is a unity and camaraderie rarely seen in any other sport. Competition exists only against the speedo, secrets are divulged, friends are made and even parts are donated by ‘opposing’ teams to help attain the miracle figures.

“It’s a big family,” says JP of his experiences. “The first year we went to Lake Gairdner and got scrutineered (ensuring their bike complies with regulations), we thought we’d done everything to specification but we had to change our fuel line. We were in the middle of the desert and had no way of getting a new fuel line. But some guy just came out of nowhere and gave us five metres of fuel line and said, ‘just pay me back later.’

“Everyone has worked hard just to get to the salt, so everyone looks out for each other.”

The bikes, unsurprisingly, aren’t road legal and are so loud that they can’t even be so much as started in residential areas, so often, the only moments a bike will ever be ridden is on the salt. JP has run his bike on a private Gold Coast runway on occasion, but it is nowhere near long enough to replicate a world record attempt or test the bike to its full capacity. But he and his team have proved themselves. They have shown that they are a whisper short of the record and that they are every bit deserving of their chance to run at Bonneville.

With the help of sponsorship from national and local business, JP, Mitch and their dad are on their way. The bike is in a crate somewhere on the Pacific, the tickets are booked and a fellow salt addict (who they have never met, yet connected with through their passion) has promised to collect the bike and lend them the use of his truck to get to Bonneville. In just nine weeks’ time, a new world champion may be heading back home.

We may not be gifted or blessed in the life we are born into, we may be, for all intents and purposes, ‘normal’ – if there even is such a thing. But however unremarkable we may be, our potential will only ever be hindered by the choking grasp of our own two hands. If you aim for the horizon, you just might get there fastest.

JP Afflick would like to thank the generous support of all his sponsors, including local businesses:

- Brookfarm

- Bay Seafood

- Danny Wills Quiksilver, Byron Bay

- East Point Signs

You can follow the pursuits of JP and team AAA Racing on their road to Bonneville at – www.facebook.com/AAALandSpeedRacing

– This article first appeared on Common Ground Australia on Jun 4, 2015

CD COVER DESIGN

THIS ARTICHOKE HEART

You May Also Like

THIS ARTICHOKE HEART

June 17, 2015

BUN COFFEE | COOL BEANS

June 2, 2015