THE CHANGING TIDE | REFLECTING SURF CULTURE

Since it first fell into Western hands, surfing has existed in a state of flux. It is in our nature to want newer, better, faster of our frivolous possessions. We upgrade our technology, succumb to the whim of fashion and expand our material wealth as if these are the makings of a better life. We have inflicted these ideals upon surfing, advancements in manufacturing and design whittling away at boards until they have become almost completely disconnected from their hand-hewn timber forebears.

But, as a certain musical poet once warbled, the times, they are a-changing – the lifelong mantra of the sport of kings. It’s tricky to pinpoint the moment it occurred, or by whose hand it was instigated, but over the past decade, there has developed within the oceanic community a return to creativity. In its many guises, it has manifested in a reconnection with local shapers, in myriad art forms and in the salt stained garments in which we clothe ourselves. In fact, for a growing subculture, it has permeated every waking hour of our existence. Perhaps it is a metamorphosis of the greater social conscience, but surf culture is most certainly leading the charge.

“Surfers don’t just surf in general,” reflects French surfer-filmmaker, Romain Juchereau. “They associate a lifestyle with it; living by the sea, breathing a purer air, embracing the nature that surrounds them, and some of them need to express their feelings of what the sea and the surf give them. That is when the magic happens. If you are a surfer and you are even minimally creative, you would definitely give it a go at expressing yourself in one way or another and getting involved in the surf culture because that is what we live for.

“Nowadays,” he continues, “people have more opportunities and options to show their creativity and express themselves. When cameras and video cameras appeared many years ago, a new window opened onto the surf culture for creative people. I guess only for the people who could afford it at first, but then cameras became more affordable and the surf photography was born.

“Of course, technology has made surf culture evolve too, in its own way, the internet and social media helping to spread the word much more quickly than ever before.”

This is the premise of Romain’s recent film, Behind The Tide, an introspection on a global tribe, interwoven, hermitic, but all following the same path. For some, the creative outlet of a brackish existence is as literal as shaping their own boards, planing away in their folks’ garage with the simple reward of riding something borne of their own two hands, functional or not. But for others, a weekend project is not enough. It is these individuals who are subject to Romain’s lens, those who not only reflect their love of the ocean on terra firma but who have made it their entire lives.

Noosa’s Thomas Bexon and Jake Bowrey drew Romain’s attention on a visit to Australia in 2013. In many respects, they are a shaper and a glasser, respectively, much like any other, but the philosophy behind their business is distinctly different. Of course, sustaining themselves financially is a focus, but never at the expense of their moral perspectives. They shape the boards they believe in, the craft they’d choose, not catering to the surfing public at large, but fulfilling the niche that inspires them and, in so doing, creating boards that exude the passion with which they are made.

From the southwestern corner of England, James Otter crafts boards from timber, using traditional techniques in shaping and joinery to create boards as much functional as they are masterpieces. Recognising the need for sustainability in a toxic industry and pursuing his ardor for creativity, his career has been moulded by the ocean he loves and realised in the simplicity of traditional craftsmanship. Gone are any delusions of wealth or fame, his drive instead comes from the heart, finding a way to sustain his family within the distinct boundaries of his ethics.

Pauline Beugniot was born to a surfing father on France’s south coast, finding her love for the sea both in and out of the water. Her artwork is an embodiment of the joy she feels in riding waves, capturing the experiences that none but a surfer could reflect. Each piece gives the impression as much of an artist telling a story as an overwhelming outpouring in pen and ink of her love of the ocean, its power and its pleasures.

“I think each of these people’s mindsets is interesting because they don’t come from a corporate or competition surfing background,” suggests Romain. “They are people who live near the coast and in nature, and have found themselves an interest and a passion for surfing growing up near the sea – real people who started from scratch using their knowledge, their hands and their love for the sea and worked really hard to be where they are now.

“[In Behind the Tide] I wanted to show these talents, focusing on the people working independently, out of the mainstream, and also to show the surfing nostalgia in the renaissance of longboarding, single fin, alaia, tandem surfing and handplaning.”

Perhaps it could be seen that this diversity in equipment has given to a greater expansiveness in mindset on land as well as in the water. Surfboards no longer have to be by a particular shaper or bear brands and logos. They don’t have to be a certain shape or colour, fin set-up or material. Gone are the prejudices of even five years ago, and in their place have come a respect, a unity and an acceptance. If you’re in the water, enjoying the waves and showing common etiquette, you are welcome.

This has brought a recognition to the craftsmen and women and, as with Thomas Surfboards, a niche within which to greater express themselves. Through the 1960s and ‘70s, surfers would do anything they could to sustain their wave-hungry existence. Beg, borrow, scrimp and steal, they were social drop-outs with one sole, soul purpose: to surf.

Through the corporatisation of surfing, this was lost. Yes, you could be a professional surfer – if you were one of the 0.0000006 percent of the world’s population lucky and talented enough – but for the masses, surfing was a trend or a hobby, something you did on the weekends or outside your daily existence. Over the last decade, it has become so much more, the complete lifestyle choice exhibited in Morning of the Earth, Crystal Voyager and movies of their ilk and era. To be a surfer today is as much about the food you eat, the beer you drink, the clothes you wear, the car you drive and the career you choose as it is about your weekly wave count and encyclopaedia of manoeuvres.

“I think our generation is understanding something about the corruption and how some corporations are leading the world in some ways,” Romain hypothesises.

“Nowadays, I think people are giving more trust to the local businesses and independent brands and, as surfers, I think people like to meet and talk with the person who’s going to shape your board, glass it or paint a piece of art. For me, it’s important to know the background of the person or the company selling the thing I want to buy, because it makes such a difference in the process and this is something that businesses can’t really fake – such as experience and knowledge. So I hope that we’ll stay in this mindset and perspective of the surf culture.”

Although it is being reflected across generations, cultures and borders, this way of life is not being embodied anywhere in such proliferation as within the surfing community. Patagonia, the ecologically and ethically-minded business behind original modern-day surf hermits, the brothers Malloy, has coined the phrase, ‘Live Simply’, and is the first major corporation to tell its customers to not buy its products, but instead reflect upon what they actually need over what they simply desire. Perhaps this is nothing more than an effective marketing exercise but, whether cunningly crafted to improve sales or encourage an ethos, they stand by their words.

Upcycling has become an integral element of this lifestyle, repurposing the waste of others for new means. From creating furniture from shipping palates to using timber offcuts for handplanes, this artistry in reuse and frugality has become less the way of impoverished art students and more about artisan creativity. The sustainability in timber boards, from the most rudimentary alaias to hollow toothpicks and James Otter’s beautifully hand-crafted fishes and longboards, has shed the guise of ‘hippy bullshit’ and become instead a defining way of life.

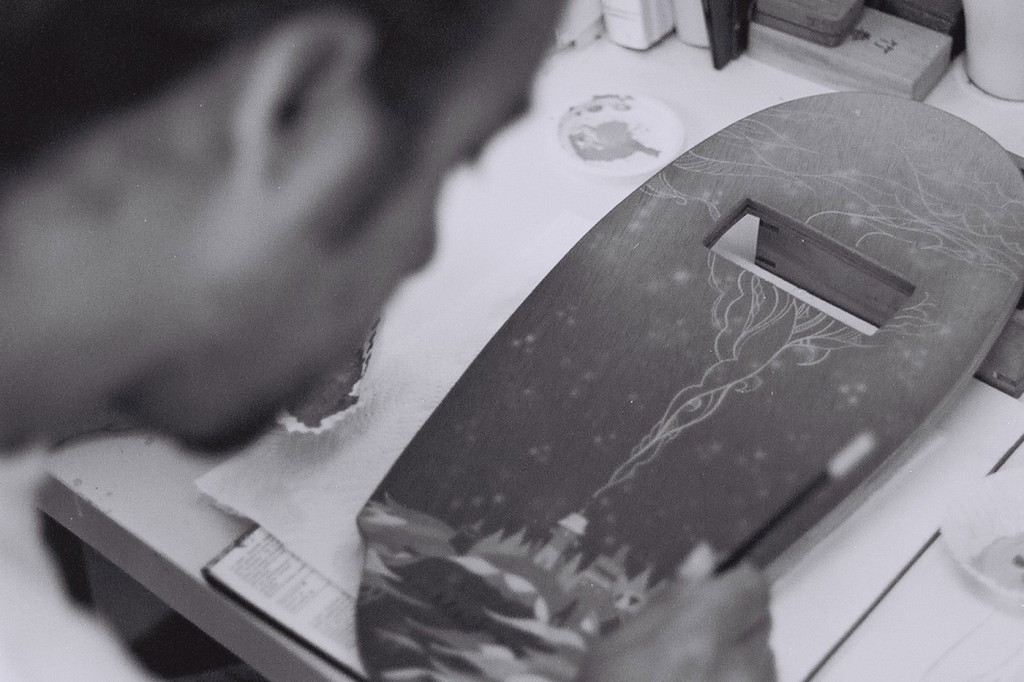

Karl Mackie has brought numerous creative elements together to exemplify this lifestyle more than almost anyone else. Graphic designer, photographer, shaper and craftsman, his life facilitates his passion in defiance of the vice versa. In Behind the Tide, Romain captures a particularly unique project, beginning with Mackie’s simple timber handplanes. Although a superb shaper of conventional surfboards, Mackie embraces the most basic of surfing forms in bodysurfing, shaping handplanes from a sheet of marine ply which, while perhaps not the fanciest of surf craft, are the definition of functionality.

These are then sent across the world to surfer artists, adorned with exquisite imagery, exhibited and finally finding their way into the hands of, among others, renowned photographer and filmmaker, Nathan Oldfield.

“I think, nowadays, the surfing world has become so vast,” says Oldfield as the movie rolls. “There’s people all around the world surfing in so many different ways for so many different reasons and riding all kinds of craft. But, on the other hand, I think that surfing can still be small and intimate and connected. I guess this handplane is the perfect example of that.”

We have come to a place in our collective mentality as surfers – through the inception of foam, the addition of numerous fins, the exploration of the past and the commercialisation of this most natural of sports – that can no longer be packaged or branded, marketed or copyrighted. We have risen above the prescribed notions of what a surfer must be, holding the value of this precious lifestyle above any fashion or advertising campaign.

“I think it’s important to take note of these perspectives because it makes you think and understand why we are doing what we do, ” says Romain, “what joy it brings us when we make something from an interaction with our passion, the joy of creating something unique, and the pleasure to share it with others with the same mindset.

“This is what I wanted to show with the little handplane story in the film; starting with a Cornish shaper bringing this wooden handplane to life using basic tools in his back garden shed, then getting painted by a local artist in a fisherman’s village in Cornwall using brushes and paint to finally end up in Australia, in the hands of Nathan Oldfield, surf filmmaker, photographer, and surfer, who is bodysurfing with that little handplane on the other side of the planet. To me, it was just fantastic.”

Behind the Tide stands as visual testament to this change of tide, the becoming of a more organic future, absent of materialistic consumerism and a journey towards sustainability in all that we do. Finally, we have become more than our bank accounts and possessions, finally, we measure wealth in our joys, our passions and our joie de vivre and no longer by our servitude to social dogma and monetary growth.

Long live the revolution.

– This article first appeared in the June 2015 issue of Foam Symmetry Magazine

Photos: All kindly courtesy of ©Romain Juchereau

SOULCAGES

You May Also Like

WE, THE COMPLACENT

May 30, 2015

PULP FRICTION

July 9, 2016